Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution

Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution Why Read Moby-Dick?

Why Read Moby-Dick? Second Wind: A Nantucket Sailor's Odyssey

Second Wind: A Nantucket Sailor's Odyssey The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn In the Heart of the Sea: The Epic True Story That Inspired Moby-Dick

In the Heart of the Sea: The Epic True Story That Inspired Moby-Dick Away Off Shore: Nantucket Island and Its People, 1602-1890

Away Off Shore: Nantucket Island and Its People, 1602-1890 The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull and the Battle of the Little Big Horn

The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull and the Battle of the Little Big Horn Second Wind

Second Wind Away Off Shore

Away Off Shore The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World*

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World* Sea of Glory

Sea of Glory In the Heart of the Sea

In the Heart of the Sea The Last Stand

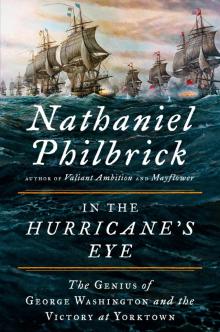

The Last Stand In the Hurricane's Eye

In the Hurricane's Eye